Greatness is in the eye of the beholder

This article was inspired when Terry McLaurin achieved a new milestone for Commanders’ receivers in the final game of the otherwise milestone-poor 2023 season. With 1:06 remaining, in the fourth quarter, and Washington trailing the Cowboys 38-10, Terry caught a 15 yard pass from Sam Howell to become the first receiver in franchise history to record four 1,000 yard seasons in his first five years with the club.

While most in the fanbase were celebrating a great achievement by one of the team’s few stars, in an otherwise forgettable season, I had a problem with it. Terry was only able to notch is fourth consecutive 1,000 yard season because the NFL extended the regular season to 16 games in 2021. The other players with whom Terry was being compared only had the benefit of playing 16 or fewer games in a season. On a level playing field with other receivers since 1978, Terry would have actually only notched two 1,000 yard seasons, since he went over the 1,000 yard mark in the 17th game of the 2021 and 2023 seasons.

Let me be clear, this is not an attempt to knock some of the shine off of Terry McLaurin’s early receiving career in Washington. What he has achieved in his first five seasons holds up as quite possibly the fastest start to a receiver’s career in franchise history, depending on how you measure it. His consistent high level of achievement is particularly remarkable, given the inconsistency of the quarterbacks throwing him the ball, and the teams they have played for. There is every reason to believe that, in a stable team environment he could eventually challenge the greatest receivers to play in burgundy and gold. But I don’t think there is any case to be made that he has got there already.

Rather, the dubious franchise record which was created for Terry got me thinking about how we identify “greatest” accomplishments and players in franchise history. As we will see, the metrics that are normally used to bestow these sorts of honors have a strong recency bias.

At this pivotal moment for the Commanders, I thought it would be fun to look all the way back through team history to identify all the players with claims to being the greatest receiver in franchise history. This will include receivers who played in regular seasons ranging from nine through 17 games, and those who played before various rule changes which have made it increasingly easier to accumulate large receiving totals throughout the decades.

My initial impulse was to use the field-levelling approach I took in last offseason’s search for the greatest quarterback in NFL history. However, rather than impose my opinion of who deserves the title of Greatest Receiver in Franchise History, I opted instead to put forward four different alternative viewpoints for readers to debate. There are arguments to be made for at least four different players. Rather than attempting to narrow the spotlight, I felt it would be more fun and informative to attempt to broaden it.

Speaking of team history, you may have noticed that I used the unfashionable R-word in the title. I chose that name for a reason, and it wasn’t just to stir up the name debate. Ordinarily, when I need to refer to the team across a span of more than one name, I call them ‘Washington’. In this case, however, I will be looking all the way back to the team’s origin in Boston, and considering receivers who played for the team under the names Braves, Redskins, Football Team and Commanders. Rather than call them ‘Boston/Washington’, I opted for the less awkward ‘Redskins’. Without giving too much away, all of the serious contenders for franchise GOAT honors played in a Redskins uniform.

Career Receiving Totals

The usual approach to bestowing all-time franchise honors is based on cumulative career totals, so let’s start there. The following table lists the top 10 receivers in franchise history, ranked by career regular season receiving totals. Data are straight out of Pro Football Reference.

I have some quibbles with recognizing greatness based on cumulative totals, but it is hard to argue with the name at the top of the list. Art Monk was the lead receiver throughout the Redskins’ second championship era under Head Coach Joe Gibbs and General Manager Bobby Beathard. He made critical catches in two Super Bowls and 14 playoff games in a 14 year career for the Redskins. Monk is a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame and the Hall of Fame All-1980s Team, and was nominated two All-Pro teams and three Pro Bowl Rosters.

Art Monk sets the standard for claims to being the greatest receiver in franchise history. This article would end here if I didn’t think there were other players with arguments to make. But they will have to be very strong arguments to knock Monk off the throne.

My issue with cumulative career totals is that they don’t differentiate greatness from being very good for a long time. Two players on the franchise top ten list never even led the team in receiving yards for a season. Jerry Smith and Chris Cooley were both very good tight ends for the Redskins in their day. Smith led the team in scoring in 1967, but neither he nor Cooley ever led the team in receiving yards. Smith and Cooley make the franchise top ten list by virtue of having sustained high levels of production over long times, without ever having achieved elite status.

Some might argue that maintaining high average production over a long period is worthy of franchise honors. But I think the term ‘greatest’ implies more than that.

Peak Seasons

Another approach which might come closer to the mark is counting the peaks of production that players have achieved in their careers. This is the type of honor that was bestowed on Terry when he went over the 1,000 yard receiving mark for the fourth season in a row.

It’s not a bad concept, but there are issues with using an arbitrary, fixed yardstick to measure all-time franchise accomplishments in a sport that has seen huge changes to the receiving game over the past last century. A 1,000 yard receiving season means a lot less now than it did during the Redskins’ first championship era.

From 1936 through 1945, the Boston and Washington Redskins appeared in six NFL Championships and won two. During that period, the NFL regular season varied from 10 to 12 games. There was no Illegal Contact rule keeping defensive backs from interfering with receivers running routes. Substitutions were limited, preventing players from specialising in offense and defense. And, most importantly, the league was only just beginning to recognize the value of the passing game, thanks in large part to the Redskins’ 1937 draft pick Sammy Baugh, who led the evolution of the passing-specialist quarterback position we know today.

The first NFL player to eclipse the 1,000 yd receiving mark was Packers’ legend Don Hutson, who shattered his own previous record of 846 yds with 1,211 receiving yards in 11 games in 1942. Hutson, by the way, has been recognized as the most statistically dominant player at any position during any era of NFL history.

McLaurin’s final catch of the 2023 season brought his season total to 1,002 receiving yards. That ranked 28th among NFL receivers that year. The NFL leader, Tyreek Hill, eclipsed McLaurin’s regular season receiving total by 797 yards, or 79.5%.

That is not meant to take anything away from Terry. It just demonstrates that the standard we use to measure peak, or even just good receiving seasons in the present era can’t be meaningfully applied to receivers playing in previous eras.

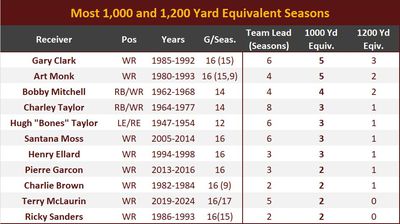

To level the playing field somewhat, I calculated 1,000 Yard Equivalent receiving totals for the leading candidates for franchise receiving GOAT honors who played in eras and seasons when the regular season was other than 16 games long. There is no way to adjust for modern era defenders having to play with their hands tied behind their back, or for quarterbacks getting much better through the years. But if we are going to compare receivers from different eras, the very least we can do is to adjust for the 70% increase in numbers of games in a season.

I chose the 16 game season as the standard because I think most fans, like me, developed their current idea of what a 1,000 yard receiving season means during the 16-game era from 1978 to 2020. A 1,000 yard total in 16 games equates to 62.5 yards per game. To calculate the 1,000 Yard Equivalent for seasons of different lengths, I simply multiplied 62.5 yards by the number of games in the regular season. This gives the receiving total that a player in a given era would have needed to achieve to have the same productivity as one who received for 1,000 yards in a 16 game season.

The 1,000 Yard Equivalent in a 17 game season is 1,062.5 yards. Therefore, Terry McLaurin actually fell short of the mark in 2021 and 2023, if we are going to make meaningful comparisons to Redskins receivers who had 1,000 yard seasons during the Gibbs/Bethard championship era.

I also feel that 1,000 yards is well short of an elite receiving benchmark in the current era, even in the 16-game seasons prior to 2021. So I also calculated 1,200 Yard Equivalents, to provide a better benchmark for receiving greatness, rather than just very goodness. The 1,000 and 1,200 Yard Equivalent benchmarks for different length regular seasons are as follows:

To compile the short list of contestants, I searched the franchise history back to the first season in 1932 to identify players with potential to have the most 1,000 Yard Equivalent receiving seasons. Even after adjusting for season length, this metric still has a hefty amount of recency bias, because it became much easier to accumulate large receiving totals after the 1940s. Nevertheless, here are the leading contenders ranked by number of 1,000 Yard Equivalent receiving seasons.

Ranking by number of 1,000 yard seasons allowed the other great receiver from the Joe Gibbs Super Bowl era to catch up with Monk. In fact, ranking by 1,200 yard seasons puts Gary Clark ahead of Art Monk as the Redskins’ all time receiving leader.

Clark seems to be remembered as the number two receiver of the 1987 and 1991 Super Bowl teams. But he was frequently the more productive of the two starting wideouts, and led the team in receiving for six seasons compared to Monk’s four. Clark was only 5’9” and 173 lbs but played much bigger than his size. Pound for pound, he was arguably the toughest wide receiver to ever play the game. His competitive toughness and knack for making big plays earned him the admiration of John Madden, who regularly featured him in his annual All-Madden teams.

Some other receivers to rise up the board when ranked by number of peak seasons are 1960s legend Bobby Mitchell and Bones Taylor, the last great receiver of the Sammy Baugh era. Henry Ellard, Pierre Garcon and founding Smurf member Charlie Brown. Brown was the team’s leading receiver during the strike-shortened 1982 Super Bowl season.

Statistical Dominance

The previous two viewpoints only consider how receivers compared to others who played for the same franchise. The third point of view looks beyond the narrow confines of a single team. If we are going to label a player the greatest receiver in franchise history, then they really should have achieved greatness at the league level.

The starting point to identify NFL greats who played receiver for Washington is to search for players who were the best receivers in the NFL in their day. In addition to raising the bar for what we call ‘great’ this approach has the added benefit of correcting for the recency bias inherent in approaches based on total receiving yardage and even adjusted peak season totals.

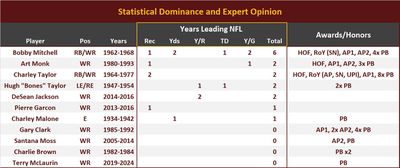

There are two common ways to identify the best receiver in the NFL in a given season or era. One is to ask how many seasons he led the league in key statistical receiving categories. This is the approach I took in my search for the greatest QB of all time last offseason. The other approach is to ask a panel of experts, which is how honors like All-Pro, Pro Bowl and Hall of Fame nominations are awarded. In this section, I will be ranking the candidates by Statistical Dominance. Awards and honors are included as validation.

To compile the short list, I carried over the names from the previous section and looked back through the entire franchise history for any other players who led the league in any season in any of the following receiving statistical categories: receptions, receiving yards, yards per reception, receiving touchdowns and receiving yards. This search turned up one new name to add to the list.

Statistical Dominance

One Redskins receiver stands out well above the others in terms of statistical dominance during three seasons at the peak of his career with the Redskins in early 1960s. Mitchell played his first four seasons with the Browns as a halfback. In 1962, he signed with the Redskins and converted to flanker, which was a back who lines up slightly behind the line of scrimmage and acts as a receiver.

That season he led the NFL with 72 receptions for 1,384 yards and 11 touchdowns. He was named first team All-Pro and finished third in MVP voting. The following season he recorded 1,436 receiving yards, which would be the equivalent of a 1,744 yard season today, if he had kept the pace for 17 games. His 1963 receiving total was the fourth highest in NFL history at the time. In three seasons he led the NFL in four different receiving categories, doubling up on receiving yards and yards per game. He also had the longest reception (93 yds) in 1963, which I didn’t count for scoring purposes.

As it turns out, only two Redskins have ever led the NFL in receiving yards. The other one, beside Mitchell, was Charley Malone who played end for the 1937 and 1942 NFL Champion Redskin teams. Malone was the Redskins’ leading receiver in 1934, 1935, 1937 and 1938. The end position was the precursor of the modern tight end. Prior to the introduction of unlimited substitutions in 1950, ends usually played on the ends of the formation on both offense and defense. Malone was a big receiver in his day at 6’4” and 206 lbs.

What makes Malone particularly special is that he set a new NFL receiving record when he led the league with 433 receiving yards in 1935. That was two years before the Redskins drafted Sammy Baugh and revolutionized the NFL passing game forever after. The previous record was 350 yards, set by the Giants Ray Flaherty in 1932.

After Bobby Mitchell, four players are tied for second place with two seasons leading a receiving category. They include Art Monk, Bones Taylor, Charley Taylor and DeSean Jackson.

Expert Opinion

By and large, the awards and honors recognizing elite players of their eras tend to agree with the statistical rankings. The most statistically dominant player, Bobby Mitchell was inducted to the Hall of Fame and was elected to two All-Pro teams and four Pro Bowl rosters. Four of the five most statistically dominant players were also recognized in their peak seasons with All-Pro and/or Pro Bowl nods. Three of the five are in the Hall of Fame.

Of the Redskins players who led the league in a receiving category for at least two seasons, only DeSean Jackson was snubbed.

Statistical Dominance is a more rarified criterion than even All-Pro and Pro Bowl nominations. Four of the Redksins’ franchise leading receivers received the latter honors without ever having led the NFL in a major receiving statistical category.

It Don’t Mean a Thing if He Ain’t Got a Ring

The previous sections rank receivers based on their achievements in the regular season, which is how franchise honors are usually awarded. Another train of thought holds that the regular season is merely a vehicle to decide which teams make it to the post-season. According to this line of thinking, greatness can only be measured in terms of championships and playoff success.

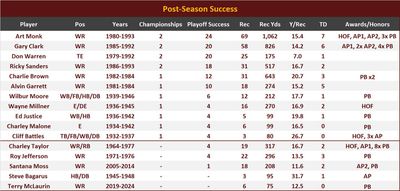

The final leaders’ board, therefore, ranks Redskins’ receivers by their contributions to NFL Championship wins (first ranking criterion) and to the team’s playoff success (second ranking criterion.

The Playoff Success metric is one I have used previously. It awards points by the highest level playoff game won in each season as follows: Wild Card 1 pt, Divisional Round 2 pts, Conference Championship 4 pts, Super Bowl 8 pts. To adapt if for this purpose, I only credited games in which the receiver in question caught at least one pass. Prior to 1966, there was a single NFL Championship game following the regular season, with an option to add a divisional round playoff game to break ties. I have treated the Championship game as a Conference Championship for scoring purposes (4 pts); while a Divisional Playoff win scored 2 pts as usual.

In one sense, this brings us back to where we started, with Art Monk reclaiming his position atop the leaders board. However, there are also some new names who did not appear in the previous rankings based on regular season receiving production.

The Redskins franchise had three eras of championship contention. Most fans today are at least familiar with the most recent championship run from 1982 through 1992. Three of the four players at the top of the board formed the Posse, who led the receiving game through the final two Super Bowl Championships of the Gibbs/Bethard era.

The two receivers who played for the team in all three of the Redskins’ Super Bowl championship seasons were Art Monk and TE Don Warren. However, Monk missed the playoffs after the 1982 season, and Warren did not make a reception in the 1991 Super Bowl. Consequently, no Redskins receiver caught a pass in three NFL Championship victories. Warren finishes third in the ranking for having made receptions in two Super Bowls wins and two Divisional Round playoff wins, despite having lower overall post-season receiving production.

Art Monk takes top honors for having contributed to more playoff victories than any other receiver in Redskins history. He also tops every other post-season receiving category except yards per reception. He also leads all Redskins receivers with four post-season games with over 100 receiving yards. His 10 rec/163 yd, 1 TD game in the 1990 divisional round loss to the 49ers was the third highest stat line by a Redskins receiver in the playoffs. He is the undisputed post-season receiving leader. Gary Clark is the clear number two.

The third member of the Posse, Ricky Sanders, had the biggest post-season game by a Washington receiver in the 1987 Super Bowl, with 9 receptions for 193 yards and 2 TDs. However, some might argue that Alvin Garrett had a bigger game in the 1982 Wild Card win over the Lions, in which he caught 6 receptions for 110 yards and became the only Redskins receiver ever to catch 3 TD passes in a playoff game.

Several Redskins receivers have caught passes in three NFL championship games, but not in three championship victories, which is how I am scoring for the all-time ranking. Players with receptions in three Championship games include Monk (1983, 1987, 1991), Wayne Millner (1936, 1937, 1940), Ed Justice (1936, 1937, 1940) and Charley Malone (1936, 1937, 1940). I mentioned Malone earlier. Millner and Justice are Redskins greats from the Sammy Baugh championship era whom fans today might not have heard about.

Wilbur Moore sits higher in the ranking because he caught passes in the 1942 Championship win and the 1943 Divisional Round playoff game. But Hall of Famer Wayne Millner was really the star receiver of the Baugh era championship teams. Millner was a 6’ 1” end on offense and defense who played for the Redskins throughout the entire duration of the first championship run. In the Redskins first Championship victory, he caught 9 passes for 160 yds and 2 TDs. Remember, this was in an era when defensive backs could contact receivers at any point on their route, and the top passers (mainly tailbacks) had reception rates below 50%. Millner’s 160 yd receiving total in the 1937 Championship is the fourth highest post-season mark in franchise history. He is also one of five Redskins with 2 TD receptions in a playoff game.

A few receivers from the previous sections who never won a championship are included below the line, as well as a few new names with notable post-season careers for the Redskins. Steve Bagarus was a half back and defensive back toward the end of the Baugh era. He caught 3 passes for 95 yards and a TD in the 1945 Championship loss. That season, season he was voted to the NFL All-Pro team, which was an official league honor back then, after leading the leading the league in punt returns (12/251, 12.0 Y/R) and yards per touch from scrimmage (10.6 yds). He also had 12 kick returns for 325 yards (27.1 Y/R) that season.

Who Is the Greatest Receiver in Franchise History?

Examining this question from four different perspectives has returned a short list of names, each of whom can make an argument to be the greatest receiver in franchise history.

Art Monk is well out in front in terms of career total receiving yards in a Redskins uniform. He also contributed to the most playoff wins, including two league championships, and leads the franchise in all but one post-season receiving categories. Furthermore, he ranked second to Gary Clark in Peak Seasons and second to Bobby Mitchell in Statistical Dominance. He remains the man to beat for all other challengers to the GOAT crown.

Gary Clark contributed to as many championship wins as Monk, and only slightly fewer playoff wins. While his career totals are no match to his illustrious team mate, he was actually more productive in a shorter career. He had more yards per reception throughout his time in Washington than Monk, and leads all receivers on the franchise leaders board in yards per game throughout his career. He was also, pound-for-pound, the toughest wide receiver in NFL history. That one is hard to quantify, but John Madden would vouch for him.

Bobby Mitchell had the misfortune of being the star of a bad Redskins team in the 1960s. Despite having Mitchell catching passes from Sonny Jurgensen, the team never posted a winning record in his time in Washington. Nevertheless, Mitchell led the league in multiple receiving categories over three season. He is the only Washington receiver who can make the claim to being the greatest receiver in the NFL at his peak, rather than just being the best receiver on the team.

Wayne Millner was the star receiver of the first Redskins championship team. His receiving statistics don’t match those of players from later eras. But he was part of the team that first demonstrated the potential of the passing game and paved the way for those who followed. He had 160 receiving yards in the Redskins first Championship win in a season when the top ranked receiver had 675 yards in the regular season and only 9 receivers had regular season totals over 200 yards. He did that before all of the rule changes to make passing easier and defending passes harder, including illegal contact and roughing the passer.